IrishCentral has put together a list of the top 100 common Irish surnames with a little explanation of where these names come from.

Whether you're looking to trace your family crest or trying to trace your family roots, this list will point you in the right direction. If your name does not appear in this list, you may find it in our comprehensive list of 300 most common Irish surnames and their meanings.

From Aherne to Whelan, here is our top 100 Irish names:

Aherne, Ó hEachtighearna / Ó hEachthairn

In Irish, Ó hEachtighearna / Ó hEachthairn, can possibly mean "lord of horses". Originally Dalcassian, this sept migrated from east Clare to Co. Cork. In County Waterford the English name Hearn is a synonym of Hearn.

MacAleese, Mac Giolla Íosa

In Irish, Mac Giolla Íosa, means "son of the devotee of Jesus". The name of a prominent Derry sept. There are many variants of the name such as MacIliese, MacLeese, MacLice, MacLise, etc. The best known of this spelling, the painter Daniel MacLise, was a family of the Scottish highlands, know as MacLeish, which settled in Cork.

Allen, Ó hAillín

This name is usually of Scottish or English origin, but sometimes Ó hAillín in Offaly and Tipperary has been anglicized Allen as well as Hallion. Occasionally also in Co. Tipperary Allen is found as a synonym of Hallinan. As Alleyn, it occurs frequently in medieval Anglo-Irish records. The English name Allen is derived from that of a Welsh saint.

MacAteer, Mac an tSaoir

Meaning "saor" or "craftsman". An Ulster name for which the Scottish MacIntyre, of similar derivation, is widely substituted. Ballymacateer is a place-name in Co. Armagh, which is its homeland. Mac an tSaoir is sometimes anglicized Wright in Fermanagh.

MacAuley, Awley

There are two distinct septs of this name, viz. MacAmhalghaidh of Offaly and West Meath, and the more numerous MacAmhlaoibh, a branch of the MacGuires, which, as MacAmhlaoibh, gives the form Gawley in Connacht. Both are derived from personal names. The latter must not be confused with MacAuliffe.

MacAuliffe, Mac Amhlaoibh

An important branch of the McCarthys whose chief was seated at Castle MacAuliffe. The name is almost peculiar to south-west Munster.

Barry, de Barra

The majority of these names are of Norman origin, i.e. de Barr (a place in Wales); they became completely hibernicized. Though still more numerous in Munster than elsewhere, the name is widespread throughout Ireland. Barry is also the anglicized form of Ó Báire (see under Barr) and Ó Beargha (meaning "spear-like", according to Woulfe), a small sept of Co. Limerick.

Blake, deBláca (more correctly le Bláca)

One of the "Tribes of Galway", an epithet name meaning "black", which superseded the original Cadell. They are descended from Richard Caddell, Sheriff of Connacht in 1303. They became and long remained very extensive landowners in Co. Galway. Branch settled in Co. Kildare where their name is perpetuated in three town lands called Blakestown.

Brennan, Ó Braonáin

The word "braon" has several meanings, possibly "sorrow" in this case. It is the name of four unrelated septs, located in Ossory (or Osraige, present-day County Kilkenny and western County Laois), east Galway, Kerry, and Westmeath. The name of the County Fermanagh sept of Ó Branáin was also anglicized to Brennan, as well as Brannan.

O'Brien, Ó Briain

A Dalcassian sept, deriving its name from historical importance from the family of King Brian Boru. Now very numerous in other provinces as well as Munster, being the fifth most numerous name in Ireland. In some cases O'Brien has been made a synonym of O'Byrne and others of the Norman Bryan.

Browne, De Brún

More correctly le Brún ("brown"). One of the Tribes of Galway. Other important families of Browne were established in Ireland from the Anglo-Norman invasion onwards. The Browns of Killarney, who came in the sixteenth century, intermarried with the leading Irish families and were noted for their survival as extensive Catholic landowners throughout the period of the Penal Laws (the Kenmare associated with their name is in Co. Limerick). The Browne family shown on the map in Co. Limerick is of Camus and of earlier introduction. Yet, another important family of the name was of the Neale, Co. Mayo. In that county Browne has also been used as a synonym of (O) Bruen.

Burk, de Burgh, de Búrca

This one of the most important and most numerous Hiberno-Norman names. First identified with Connacht, it is now numerous in all the provinces (least in Ulster). Many sub-septs of it were formed, including MacHugo, MacGibbon, Mac Seoinín (Jennings), MacRedmond, etc.

Butler

Always called deBuitléir in Irish, though it is of course properly le Butler, not de. It is one of the great Norman-Anglo names, which, however, did not soon become hibernicized like the Burkes, etc. Historically, it is mainly identified with the Ormond country. It is now very numerous in all the provinces except Ulster.

MacCabe, Mac Cába

A galloglass (from Irish: "gall óglaigh" means foreign warriors) family with the O'Reillys and the O'Rourkes, which became a recognized Breffny sept. Woulfe suggests "cába" ("cape"), a surname of the nickname. Having regards to their origin, it is more likely to be from a non-Gaelic personal name.

Callaghan, Ó Ceallacháin

The derivation from "ceallach", meaning "strife", which usually given, is questioned, but no acceptable alternative has been suggested. The eponymous ancestor in this case was Ceallacháin, King of Munster (d. 952). The sept was important in the present Co. Cork until the seventeenth century and the name is still very numerous there. The chief family was transplanted under the Cromwellian regime to east Clare, where the village of O'Callghan's Mills is called after them.

Campbell, Mac Cathmhaoil

From Irish "cathmhaoil", meaning "battle chief". An Irish sept in Tyrone; in Donegal it is usually of Scottish galloglass origin, viz. Mac Ailín a branch of the clan Campbell (whose name is from "cam béal", meaning "crooked mouth"). Many Campbells are of more recent Scottish immigrants. See MacCawell. The name has been abbreviated to Camp and even Kemp in Co. Cavan.

MacCarthy, Mac Ćarthaigh

Meaning "son of Cárthach", from Irish "cárthach" - "loving". The chief family of the Eoghanacht and one of the leading septs of Munster, prominent in the history of Ireland from the earliest times to the present. MacCarthy is the most numerous "Mac" name in Ireland.

Cassidy, Ó Caiside

A Fermanagh family of ollavs (professors or learned men) and physicians to the Maguires. Now numerous in all the provinces except Connacht.

Clery, Cleary, Ó Cléirigh

From Irish "cléireach", meaning "clerk". One of the earliest hereditary surnames. Originally of Kilmacduagh (Co. Galway), the sept was dispersed and after the thirteenth century settled in several parts of the country; the most important branch were in Donegal, where they became notable as poets and antiquaries. In modern times, the name is found mainly in Munster and Dublin.

O'Connor, Ó Conchobhair

The name of six distinct and important septs. In Connacht there were O'Connor and O'Conor Don (of which was the last High King of Ireland), with its branches O'Conor Roe and O'Conor Sligo; Also O'Conor Faly (i.e. of Offaly), O'Connor Kerry and O'Connor of Corcomroe (north Clare). The prefix, "O", formerly widely discarded, has been generally resumed. Similarly the variant from Connors has been O'Connor again.

(O) Conroy, Conree, Conary, Conry

These mainly Connacht names, owing to the similarity of the anglicized forms, have become virtually indistinguishable. They represent four Gaelic originals, viz. Mac Conraoi (Galway and Clare), Ó Conraoi (Galway), Ó Conaire (Munster), and Ó Maolchonaire (an important literary family of Co. Roscommon).

Cooney, Ó Cuana

Originally of Tyrone, this family later migrated to north Connacht. The Cooneys of east Clare and south-east Galway may be of different origin. (For the probable derivation see Coonan.)

MacCormack, Cormick, Mac Cormaic

This name, just like MacCormican, is formed from the forename Cormac. It is numerous throughout all the provinces, the spelling MacCormick being more usual in Ulster. For the most part it originated as a simple patronymic; the only recognized sept of the name was of the Fermanagh-Longford area. Many of the MacCormac(k) families of Ulster are of Scottish origin, being a branch of the clan Buchanan-MacCormick of MacLaine.

Daly, Dawley, Ó Dálaigh

From Irish "dálach" or "dáil", meaning "assembly". One of the greatest names in Irish literature. Originally from West Meath, with sub-septs in several different localities. As that in Desmond, it appears in the records as early as 1165 - it is probable that this was a distinct sept.

Darcy, Ó Dorchaidhe

From "dacha", meaning "dark" in Irish. One of the "Tribes of Galway", also anglicized as Dorsey, it is the name of two septs, one in Mayo and Galway, the other in Co. Wexford.

(O) Delaney, Ó Dubhshláine

Meaning "descendant of Dubhshláine" or "Dubhshláinge" ("black of the Slaney"). The prefix "O" has been completely discarded in the anglicized form of the name. It appears as Delane in Mayo. Both now and in the past, it is of Leix (County Laois) and Kilkenny.

(O) Dempsey, Ó Díomasaigh

From Irish "díomasach", meaning "proud". A powerful sept in Clanmalier. O'Dempsey was one of the very few chiefs who defeated Strongbow in a military engagement. Many of his successors distinguished themselves as Irish patriots and they were ruined as a result of their loyalty to James II. The name is now numerous in all the provinces.

Disney

Derived from a French place-name, Isigny-sur-Mer, and originally written D'Isigny, "from Isigny", the name Disney occurs quite frequently in the records of several Irish counties in the south and midlands since the first half of the seventeenth century.

(O) Dolan, Ó Dúbhláin

The general accepted form in Irish today is Ó Dúbhláin (mod. Ó Dúláin) as given by Woulfe and others. O'Dolean, later Dolan, derives from Ó Dobhailen, the name of a family on record since the twelfth century in the baronies of Clonmacnowen, Co. Galway, and Athlone, Co. Roscommon, in the heart of the Uí Mainecountry and quite distinct from Ó Doibhilin (Devlin). There has been a movement north-eastwards so that now the name Dolan is numerous in Co. Leitrim, Fermanagh, and Cavan as well Co. Galway and Roscommon.

Mac Donagh, Mac Donnchadha

Meaning "son of Donagh". A branch of the MacDermots of Connacht, where the name is very numerous. In Connemara, the name is usually that of a branch of the O'Flahertys. The MacDonagh sept in Co. Cork were a branch of the McCarthys: the name is now rare there and, apparently, many of these resumed the name MacCarthy.

O'Donnell, Ó Domhnaill

The main sept, one of the most famous in Irish history, especially in the seventeenth century, is of Tirconnell; another is of Thomond, and a third of the Uí Maine (Hy Many, in Co. Galway).

(O) Donoghue, Donohoe, Ó Donnchadha

An important sept in Desmond: where the name was perpetuated in the territory called Onaght O'Donoghue. There also were two others in Counties Galway and Cavan, where the spelling Donohoe is usual. According to Dr. John Ryan, there was another O'Donoghue sept in Co. Tipperary of Eoghanacht descent.

O'Dowd, Dowda, Doody, Duddy

This is one of the 'O' names with which the prefix has been widely retained, O'Dowd being more usual than Dowd. Other modern variants are O'Dowdy and Dowds, with Doody, another synonym, found around Killarney. O'Dowd, which comes from Ó Dubhda, which means "black" or "dark complexioned", was first found in county Mayo. A branch settled in Kerry where they are called Doody. Another small sept of Ó Dubhda is in Co. Derry and they are usually Duddy now.

Doyle, Ó Dubhghaill, MacDowell, Mac Dowell, Mac Dubhghaill

Meaning "descendant of Dubhghaill ("dark stranger")". This is the Irish from of the name of the Scottish family of Macdugall, which came from the Hebrides of galloglasses, and settled in Co. Roscommon, where Lismacdowell locates them. Doyle, rarely found as O'Doyle in modern times, stands high on the list of Irish surnames arranged in order of numerical strength, holding the twelfth place with approximately 21,000 people out of a population of something less than 4 million. Though now widely distributed, it was once most closely associated with the counties of southeast Leinster (Wicklow, Wexford, and Carlow) in which it is chiefly found today, and in the records of the fifteenth, sixteenth and seventeenth centuries.

(O) Duffy, Ó Dubhthaigh

Duffy or O'Duffy is a numerous name in all of the provinces except Munster. Modern statistics show that is now the most numerous name in Co. Monaghan.

(O) Dwyer, Ó Duibhir

From "dubh" and "odhar", gen. "uidhir", meaning "duncoloured". Of Kilnamanagha, a leading sept in mid-Tipperary. A great name with resistance to English domination.

Mac Fadden, Fayden, Mac Pháidín

From "Paídí n", a diminutive of Pádraig or Patrick. An Ulster name, of both Scottish and Irish origin. Without the "Mac", it is found in Mayo.

Fanning, Fannin, Fainín

A Name of Norman origin, prominent in Co. Limerick, where Fanningstown, formerly of Ballyfanning, indicates the location. They were formerly of Ballingarry, Co. Tipperary, where in the fifteenth century the head of the family was, like Irish chiefs, officially described as "captain of his nation". Fannin is a variant.

Fitzgerald, Mac Gerailt

One of the two greatest families, which came to Ireland as a result of the Anglo-Norman invasion. It had two main divisions, Desmond (of whom are the holders of the ancient titles Knight of Kerry and Knight of Glin); and Kildare, whose leaders held almost regal sway up to the time of the Rebellion of Silken Thomas and the execution of Henry VIII of Thomas and his near relatives in 1537. The bane is now very numerous.

Fitzpatrick, Mac Giolla Phádraig

Meaning "devotee of St. Patrick". The only Fitz name of Gaelic-Irish origin, the main sept being located in Ossory (or Osraige, present-day County Kilkenny and western County Laois). The name is numerous also in Fermanagh, where families so called are said to be of MacGuire stock.

O'Flaherty, Laverty

From "Flaithbhertaig", meaning "bright leader". The O'Flahertys possessed the territory on the east side of Lough Corrib until the thirteenth century when, under pressure from the Anglo-Norman invasion into Connacht, they moved westwards to the other side of the lake and became established there. The head of the sept was known as Lord of Moycullen and as Lord of Iar-Connacht, which, at its largest, extended from Killary Harbour to the Bay of Galway and included the Aran Islands.

Flanagan, Ó Flannagáin

From "flann", meaning "ruddy" or "red". Of the several septs of the name that of Connacht is the most important: their chief ranked as one of the "royal lords" under O'Connor, King of Connacht.

Flood

Some Floods are of English extraction, but in Ireland they are plainly Ó Maoltuile or Mac Maoltuile, abbreviated to Mac an Tuile and Mac Tuile anglicized MacAtilla or MacTully as well as Flood. Tuile means "flood" but probably it is here for "toile", gen. of "toil" or "will", i.e. the "will of God". In parts of Ulster, Flood is used for the Welsh Floyd. (Welsh llwyd. Grey).

(O) Flynn, Flyng, Ó Floinn

Another name derived from "flann", meaning "ruddy". This numerous and widespread name originated in a number of different places, including Kerry and Clare. Of the two in Co. Cork one was a branch of the Corca Laoidhe, the other, lords of Muskerylinn (Muiscre Uí Fhloinn); in north Connacht the O’Flynns were leading men under the royal O’Connors, and there was also an erenagh family there; while further West on the shores of Lough Conn another distinct erenagh family was located. For the name in Ulster is an indigenous sept.

(O) Gallagher, Ó Gallchobhair

This name, from "gallchobhar" (meaning "foreign help"), has at least 23 variant spellings in anglicized forms, several of them beginning with Gol instead of Gal. It is that of one of the principal septs of Donegal.

MacGowan, Mac an Ghabhann, Mac Gabhann

In Co. Cavan, the homeland of this sept, the name has been widely changed by translation to Smith (though Smithson was a truer translation); but in outlying areas of Breffny MacGowan is retained.

(O) Grady, Ó Grádaigh

From "gráda", meaning "illustrious". A Dalcassian sept. The leading family went to Co. Limerick, but the majority are still in Clare, where the prefix "O" is retained more than anywhere else. An important branch changed their name to Brady in the late sixteenth century. The well-known name Grady has to a large extent absorbed the rarer Gready, which is properly a Mayo name. This resulted in the name of Grady being numerous in north Connacht and adjacent areas of Ulster.

MacGrath, Magrath, Mac Graith, Mag Raith

Derived from the personal name, which in this case is Craith, not Raith. The name of two distinct septs; namely (i) that of Thomond, who supplied hereditary ollamhs in poetry to the O'Briens, a branch of whom migrated to Co. Wexford; and (ii) of Termon MacGrath in north-west Ulster, a co-arb family. MacGrath is often called MacGraw in Co. Down and MacGragh in Donegal.

(O) Hagan, Ó hÁgáin

It is fairly well established that this name was originally Ó hÓgáin (from "óg", meaning "young"). It is that of an important Ulster sept: the leading family was of Tullahogue. Ó hAodhagáin, also anglicized O'Hagan, is said to be a distinct sep of Oriel, but owing to proximity of Co. Tyrone and Armagh, they are now indistinguishable. The Offaly name mentioned by Woulfe is now extinct or absorbed by Egan in Leinster.

Hanlon, Ó hAluain

Possibly from "luan", meaning "champion", and intensified by "an". One of the most important of the septs of Ulster. The present association of the name with West Munster is of comparatively recent inception.

O'Hara, Ó hEaghra

An important dual sept located in Co. Sligo, the chiefs being O'Hara Boy ("buidhe") and O'Hara Reagh ("riabhach"). A branch migrated to the glens of Antrim.

(O) Healy, Hely

This is Ó hÉalaighthe in Munster, sometimes anglicized Healihy, and ÓhÉilidhe in north Connacht, derived respectfully from words meaning "ingenious" and "claimant". Ballyhelyon Lough Arrow was the seat of the altar. The Munster sept was located in Donoughmore, Co. Cork, whence was taken the title conferred on the Protestant branch.

(O) Heaney, Heeney

The Principal sept of this name is Ó hÉighnigh in Irish, important and widespread in Oriel, formerly stretching its influence into Fermanagh. Hegney is a variant. Another family of the name Ulster were erenaghs of Banagher in Co. Derry. Minor septs of Ó hÉanna (Éanna, old form of Enda), also anglicized Heaney, were of some note in Clare, Limerick, and Mayo up to the seventeenth century.

(O) Higgins, Ó hUigín

From an Old-Irish word akin to Viking, not from "uige". A sept of the southern Uí Néill, which migrated to Connacht. The O'Higgins father and son of South American fame came from Ballinary, Co. Sligo, not Ballina.

(O) Hogan, Ó hÓgain

Hogan comes from "og", meaning "young". Three septs are so called: one is Dalcassian, and one of Lower Dormond (sometimes regarded as the same); there is also one of the Corca Laoidhe.

Joyce

Though not Gaelic and sometimes found in England of non-Irish origin, Joyce may certainly be regarded as a true Irish name, and more particularly a Connacht one. The first Joyce to come to Ireland of whom there is authentic record was Thomas de Jorse or Joyce, stated by Mac Firbis (Dubhaltach Mac Fhirbhisigh) to be a Welshman, who in 1283 married the daughter of O'Briend, Prince of Thomond, and went with her by sea to Co. Galway.

Kane, O Cahan, Ó Catháin

As lords of Keenaght, the O'Kanes were a leading sept in Ulster up to the time of the plantation of Ulster. The name is still very numerous in its original homeland.

Keating

One of the earliest Hibernicized Anglo-Norman families, whose name was gaelicized Ćeitinn. They settled in south Leinster. The historian Dr. Geoffrey Keating was of Co. Tipperary. The name with the prefix "Mac" is associated exclusively with the Downpatrick area, where MacKetian is a synonym of it. The theory that Keating is derived from Mac Eitienne is improbable. Woulfe makes it toponymic. The most acceptable suggestion is that it is from Cethyn, a Welsh personal name.

(O) Kelly, Ó Ceallaigh

The derivation of Kelly is uncertain: the most probable suggestion is that it is from "ceallach", meaning "strife". The most important and numerous sept of this name is that of the Uí Maine. Kelly is the second most numerous name in Ireland. In 1890 less than one percent of them had the prefix "O", but this has been to some extent resumed.

Mac Kenna, Kennagh, Mac Cionaoith

A branch of the southern Uí Neill, mainly located in Co. Monaghan, where they were lords of Truagh; the name is now fairly numerous also in Leinster and Munster. Locally in Clare and Kelly the last syllable is stressed, giving the variants Kennaw, Ginna, Gna, etc.

Kennedy, Ó Cinnéide

From Irish "ceann", meaning "head", and "éidigh" - ugly. An important Dalcassian sept of east Clare, which settled in north Tipperary and spread thence as far as Wexford, whence came the family of President J.F. Kennedy. The Scottish Kennedys are by remote origin Irish Gaels.

Lawless, Laighléis

From the Old-English "laghles", meaning "outlaw". The name, introduced into Ireland after the Anglo-Norman invasion, is now numerous in Counties Dublin and Galway. It was one of the "Tribes of Kilkenny", but has now no close association with the city.

(O) Leahy, Ó Laochdha

From Iris "laochda", meaning "heroic". This name is very numerous in Munster but not elsewhere. It is, basically, distinct from Lahy, though they have been used synonymously.

(O) Leary, Ó Laoghaire

Laoghaire was one of the best-known personal names of Ancient Ireland. A sept of the Corca Laoidhe established in Muskerry, of importance in all fields of national activity, especially in literature, and in the military sphere both at home and as the Wild Geese.

(O) Lennon, Lenna, Ó Leannáin, Linnane, Leonard, Linnegar, MacAlinion

Possibly from "leann", meaning "a cloak" or "mantle"; "leanán", meanings "paramour", has also been suggested. This is the name of several distinct septs located respectively in Counties Cork, Fermanagh, and Galway. The last named is of the Sodhan pre-Gaelic stock. The Fermanagh family were erenaghs of Lisgoole. Ó Leannáin is also used as a synonym of Lineen (Ó Luinín), another Fermanagh erenagh family. Further confusion arises from the fact that these have been widely changed to the English name Leonard.

Mac Loughlin, Mac Lochlainn

From a Norse personal name. Of Inishowen. A senior branch of the Northern Uí Néill. They lost their early importance as a leading sept of Tirconnell in the thirteenth century, but are still very numerous in their original homeland - Counties Donegal and Derry - where their name is usually spelt MacLaughlin; MacLoughlin, also numerous, is more widespread. Minor septs in Connacht were akin to the MacDermota and the O'Connors.

Mac Mahon, Mac Mathghamhna, mod. Mac Mathúna

From "mathghamhan", meaning "bear". The name of two septs, both of importance. That of Thomond descends from Mahon O'Brien, grandson of Brian Ború. MacMahon is now the most numerous name in Co. Clare. In later times the majority of the many of the name were from the Co. Monaghan, where McMahons are numerous today, though less so in Thomond (present-day County Clare and County Limerick).

(O) Malley, Mailey, Ó Máille

From "meall", meaning "peasant" in Irish. A branch of the Cenél Eoghain located in Tyrone, where their territory was known as "O'Mellan's Country". They were hereditary keepers of the Bell of St. Patrick.

(O) Malone, Ó Maoileoin

Although Malone is a genuine 'O' name, being in Irish Ó Maoileoin (meaning "descendant of the follower of St. John"), it is never met with in English with its prefix. The Malones are an ancient sept, associated with the O'Connors of Connacht, and for centuries their principal family was associated with the Abbey of Clonmacnoise, to which they furnished many abbots and bishops. For a time Clonmacnoise was an independent see ("see", i.e. the place in which a cathedral church stands, identified as the seat of authority of a bishop or archbishop). before being united with Ardagh.

(O) Meara, Mara, Ó Meadhra

From "meadhar", meaning "merry". This well-known sept, which has produced many distinguished men and women, gave its name to the village of Toomevara, which locates their homeland. This one of the few "O" names, from which the prefix was never very widely dropped.

Molloy, Mulloy, Ó Maolmmhuaidh

The adjective "muadh", denotes "bit" and "soft", as well "noble". An important sept of Fercal in mid-Leister. Molly is an anglicized form of Ó Maolaoidh. Apart from five variant spellings, such as Maloy and Mulloy, Molloy has been officially recorded as synonym of Mulvogue (Connacht), Logue (Co. Donegal), Mullock (Offaly), Mulvihill (Kerry), and Slowey (Co. Monaghan), while Maloy has been used for MacCloy in Co. Derry.

(O) Moran

Apart from MacMorran of Fermanagh, which has inevitably been changed to Moran, there are a number of distinct septs of Ó Moráin and Ó Moghrain, whose name is anglicized Moran. Four of these are of Connacht - in which province the name is much more numerous than elsewhere - originally located (a) at Elphin in Co. Roscommon (akin to the O'Connors), (b) in Co. Leitrim (of the Muinitir Eolais), (c) in. Co. Mayo at Ardanee, (d) in Co. Galway, a minor branch of the Uí Maine. The Leitrim families are also called Morahan, as is the fifth to be enumerated, namely that of Offaly, where Morrin is a synonym.

Moynihan, Ó Muimhneacháin, Muimhneach

Meaning "descendant of Muimhneacháin" ("Munsterman"). Although there was a small sept of this name, sometimes changed to Munster, in Mayo, families so called belong almost exclusively to south-west Munster, Moynihan being very numerous on the borders of two counties. Minihan, another form of the name, is mainly found in Cork.

(O) Mulligan, Ó Maolagáin

Probably a diminutive of "maol" (see MacMullen). An important sept in Donegal, much reduced at the time of the Plantation of Ulster and now found more in Co. Mayo and Monaghan.

(O) Murphy, Ó Murchadh

Murphy is the most numerous name in Ireland. The resumption of the prefixes "O" and "Mac", which is a modern tendency with most Gaelic-Irish names, has not taken place in the case of Murphy.

(Mac) Nally, Mac Anally, Mac an Fhailghih

From "failgheach", meaning "poor man. Without the prefix "Mac" this name now is found mainly in Mayo and Roscommon; with the "Mac" it belongs to Oriel (Airgíalla in Irish, an ancient kingdom in northeast Ireland). Woulfe says that the Mayo Nallys are of Norman or Welsh oigin and acquired a Gaelic name. This is unlikely in the case of the MacNallys of Ulster as there they are often called Mac Con Ulaidh ("son of the hound of Ulidia", i.e. eastern Ulster). In the "census" of 1659 it appears as MacAnully, MacEnolly, MacNally, and Knally, all in Oriel or in counties adjacent thereto.

Mac Namara, Mac Conmara

Meaning "hound of the sea". The most important sept of the Dál gCais (Dalcassians) after the O'Briens, to whom they were marshals.

O'Neill

O'Neill is one of the proudest Irish names. It means "descended from Niall" - one of the great early Irish chieftains, Niall of the Nine Hostages. "Niall" can mean "passionate" or "champion".

(O) Nolan, Knowlan, Ó Nualláin

From "nuall", meaning "shout". In early times holding hereditary office under the Kings of Leinster, the chief of this sept was known as Prince of the Foherta, i.e. the Barony of Forth, in the present county of Carlow, where the name was and still is numerous. A branch migrated to east Connacht and Co. Longford. In Roscommon and Mayo, Nolan is used synonymously with Holohan (from the genitive plural); and in Fermanagh as an Anglicized form of ÓhUltacháin (Hultaghan). There was also a sept of the name of Corca Laoidhe, which is now well represented in Co. Kerry.

Prendergast, de Priondragás

One of the powerful families, which came to Ireland at the time of the Anglo-Norman invasion. They are still found mainly in the places of their original settlement. Some of those in Mayo assumed the name FitzMaurice.

MacQuaid, Quade, Mac Uaid

Meaning "son of Wat". A well-known name in Co. Monaghan and adjacent areas. Without the prefix "Mac" the name is also found in Co. Limerick.

(O) Quinn

Quinn is one of the most numerous Irish surnames, the number of people in Ireland so called at the present day being estimated at seventeen thousand: in the list of commonest surnames it occupies twentieth place in the country as a whole and first place in Co. Tyrone, though widespread in many counties. Tyrone is the place of origin of one of the five distinct septs of this name. The Gaelic form is Ó Cuinn, which means "descendant of Conn".

(O) Rafferty, Ó Raithbheartaigh, mod. Ó Raifeartaigh

Though etymologically this name (from "rath bheartach", meaning "prosperity wielder") is distinct from Ó Robhartaigh (from "robharta", meaning "full tide") anglicized O'Roarty, these two names have been treated as one, at least since the fifteenth century. As co-arbs of St. Columcille on Tory Island, Roarty is now mainly in Co. Donegal, while Rafferty is of Co. Tyrone and Co. Lough.

(O) Rahilly, Ó Raithile

This well-known Munster family originated as a branch of the Cenél Eoghain in Ulster, but has long been closely associated with west Munster. The poet Egan O'Rahilly, for example, was a Kerryman.

Redmond, Réamonn

A Hiberno-Norman family of importance throughout Irish history. They are associated almost entirely with South Wexford. The branch of the MacMurroughs in north of that county, some of whom adopted the name of Redmond, whose chief was called Mac Davymore, are quite distinct from the MacRedmonds.

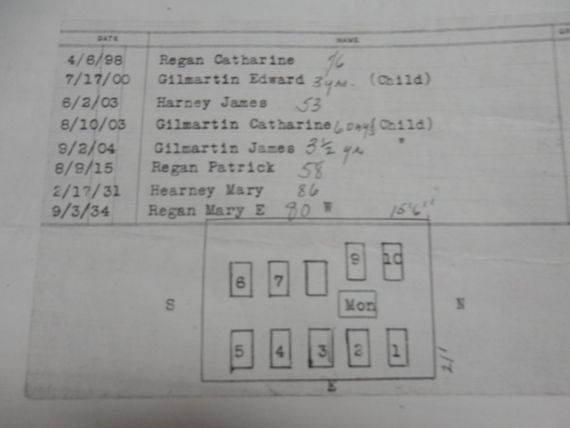

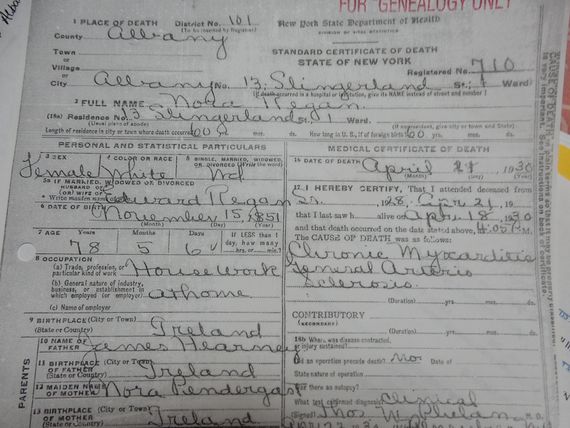

(O) Regan, Ó Riagain

Ó Réagain is used in county Waterford. There are three septs with this name. That shown as of Leix (Co. Laois) was in the early times one of the "Tribes of Tara". The eponymous ancestors of the Thomond sept were akin to Brian Boru. The third was akin to the MacCarthys.

(O) Reilly, Ó Raghailligh

One of the most numerous names in Ireland, especially so in Co. Cavan. The prefix "O" has been widely resumed in the anglicized form. The head of this important sept was chief Breffny O'Reilly.

(O) Riordan, Rearden, Ó Riordáin

This numerous sept belongs exclusively to Munster, the earlier form of Ó Rioghbhardáin reveals its derivation from "riogh bhard", meaning "royal bard" in Irish.

(O) Rooney, Ó Ruanaidh

Originating in Co. Down, where Ballyroney locates them, this name is now numerous in all of the provinces, except Munster. In West Ulster and north Connacht, Rooney is often an abbreviation of Mulrooney.

Ryan, (O) Mulrian

Ryan is amongst the ten most common surnames in Ireland with an estimated population of 27,500. Only a very small proportion of these use the prefix 'O'. Subject to one exception, to be noticed later in this section, it is safe to say that the great majority of the twenty-seven thousand five hundred Ryans are really O'Mulryans - this earlier form of the name is, however, now almost obsolete. First found in Tipperary.

(O) Shea, Shee, Ó Séaghdha; mod. Ó Sé

From "séaghdha", meaning "hawklike", secondary meaning "stately". Primarily a Kerry sept, but (as in Shee) it is notable as the only Gaelic-Irish name among "the Tribes of Kilkenny", to which county and Co. Tipperary a branch of the sept migrated in the thirteenth century.

(O) Sheehan, Sheahan, Ó Síodhacháin

The obvious derivation from "síodhach", meaning "peaceful", is not accepted by some Celtic scholars. The Dalcassian sept, which spread southwards, accounts for the majority of Sheehans, who are now very numerous in Counties Cork, Kerry, and Limerick. Formerly, there was also an Uí Maine sept of this name, which, however, is rarely found in Connacht today.

(O) Slattery, Ó Slatara, Ó Slatraigh

From "slatra", meaning "strong". Of Ballyslatterly in east Clare. The name has now spread to adjacent counties of Munster.

Smith, Smyth

When not the name of an English settler family, Smith is usually a synonym of MacGowan, nearly always so in Co. Cavan.

(Mac) Spillan(e), Mac Spealáin

Sometimes appears as a derivation of O'Spillane, this family name is, however, quite distinct from Ó Spealáin (O'Spillane). Spollan and Spollin, rarely retaining the prefix Mac, are numerous in County Offaly. Older anglicized forms were Spalane and Spalon.

(O) Sullivan, Ó Súileabhain

While there is no doubt that the basic word is "súil" ("eye"), there is a disagreement as to the meaning of the last part of the name. This is the most numerous surname in Munster and is third in all of Ireland. Originally of south Tipperary, the O'Sullivans were forced westwards by the Anglo-Norman invasion where they became one of the leading septs of the Munster Eoghanacht. There were several sub-septs, of which O'Sullican Mor and O'Sullivan Baere were the most important.

(Mac) Sweeney, Swiney, Mac Suibhne

The word "suibhne" denotes "peasant", the opposite of "diubhneI". Of all galloglass origin, it was not until the fourteenth century that the three great Tirconnell septs of MacSweeney were established; more than a century later a branch went to Munster.

(O) Tierney, Ó Tighearnaigh

From "tighearna", meaning "lord" in Irish. There were three septs of this name, in Donegal, Mayo, and Westmeath, but it is now scattered. It is much confused with Tiernan in Mayo. In southern Ulster this name is usually of different origin, namely Mac Giolla Tighearnaigh, which was formerly also anglicized MacIltierney.

Walsh, Ó Breathnach

Ó Breathnach, meaning "Breton," "Welshman," or "Foreigner", which is re-anglicized also as Brannagh, Brannick, etc. A name given independently to many unconnected families in different parts of the country and now the fourth most numerous of all Irish surnames. It is sometimes spelt Welsh, which is the pronunciation of Walsh in Munster and Connacht.

(O) Whelan, Ó Faoláin

From Irish "faol", meaning "wolf". A variant form of Phelan numerous in the country between Co. Tipperary and Co. Wexford. Whelan is also sometimes an abbreviation of Whelehan and occasionally a synonym of Hyland. Whelan is rare in Ulster.

.jpg)

Bridget was the fifth eldest of nine children who lived in a cottage with no bath or electricity. She occasionally went to school barefoot. Older siblings Mary and Michael emigrated to the United States, both settling in Glen Falls, where Mary became a domestic and her brother a fireman. On discharge from the hospital, a penniless Bridget was assisted by the American Red Cross, receiving $125. She worked as a domestic in Glen Falls for two years before moving to New York and becoming engaged by the wealthy Nicholls family.

Bridget was the fifth eldest of nine children who lived in a cottage with no bath or electricity. She occasionally went to school barefoot. Older siblings Mary and Michael emigrated to the United States, both settling in Glen Falls, where Mary became a domestic and her brother a fireman. On discharge from the hospital, a penniless Bridget was assisted by the American Red Cross, receiving $125. She worked as a domestic in Glen Falls for two years before moving to New York and becoming engaged by the wealthy Nicholls family.